As we enter the next era of space exploration, the focus is shifting from launching missions to constructing advanced in-space infrastructure, with one major obstacle standing in the way: the growing threat of space debris. The billion-dollar question of who bears the cost of space debris cleanup has been a longstanding issue, directly tied to uncertainty about liability and the lack of incentives. Over the past decades, this issue has been a game of hot potato between governments, space agencies, and the industry with marginal progress.

| Active debris removal faces a catch-22: high development costs and unproven technology make it difficult to attract investment, while the industry is hesitant to commit without validated, cost-effective solutions. |

Currently, there’s no clear funding mechanism for active debris removal (ADR) activities beyond the space agencies’ investments, leaving the “tragedy of the commons” unresolved. Various models, including regulatory fees, taxes, tradeable permits, and cleanup funds, have been suggested, highlighting the need for international cooperation. However, achieving consensus remains challenging especially in current geopolitical environment. Additionally, balancing environmental sustainability with industry impact is crucial for successful adoption. What follows is a framework that aims to strike this delicate balance.

The problem: space debris and the issue of incentive

The growing problem of space debris has been debated for decades and is now at the forefront of sustainability discussions. Currently, there are 36,860 tracked objects in space. With a record-high 223 launches in 2023 and projections of another 36,900 objects entering space by 2033, the collision risk is increasing exponentially. Recent incidents of space junk hitting Earth are increasingly making headlines, raising public awareness. With unprecedented space activity, rising collision risks, and the debris issue now in the public eye, it’s necessary to transition from discussions to actions.

Managing space debris requires an integrated approach, combining debris avoidance, limiting debris creation (mitigation), and debris removal (remediation). Significant progress has been made in debris avoidance, through improved tracking and development of space situational awareness (SSA) capabilities. While various debris mitigation guidelines exist, they are all non-binding, leading to voluntary and thus suboptimal compliance, especially in LEO. Initiatives like ESA’s Zero Debris Charter and the UK’s Astra Carta are aimed at encouraging sustainable practices, but participation remains voluntary, attracting industry players with existing commitment to sustainability. These initiatives also do not address accumulation of debris over the past decades.

While debris avoidance and mitigation efforts have seen some momentum, remediation, or ADR, has significantly lagged behind. The root of the issue lies in the regulatory environment, which lacks both incentives and penalties to promote compliance and sustainable practices. Despite widespread recognition of the problem, the absence of binding regulations, financial incentives, and proven technologies continue to hinder meaningful progress. ADR faces a catch-22: high development costs and unproven technology make it difficult to attract investment, while the industry is hesitant to commit without validated, cost-effective solutions. This creates a vicious cycle, with supply side requiring demand to mature, but the demand side is reluctant to invest without proven capabilities and regulatory pressure. Without intervention, the market has no inherent need to bridge this gap. Therefore, government action—through binding regulations and incentives—is essential to break this deadlock and enable the development of the ADR market.

Pioneering companies like Astroscale, Starfish Space, Kall Morris, and D-Orbit are diligently working to prove the technology, relying on a handful of government sponsored missions. The question remains: can they sustain their efforts long enough for the necessary market conditions and regulatory framework to materialize?

The solution: Orbital Tollway Framework

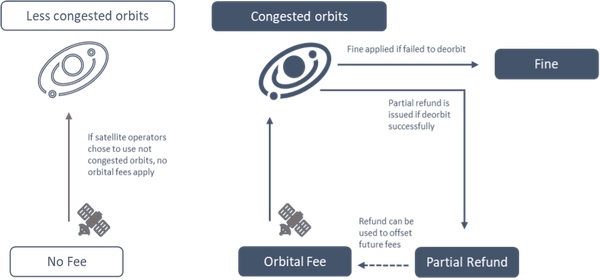

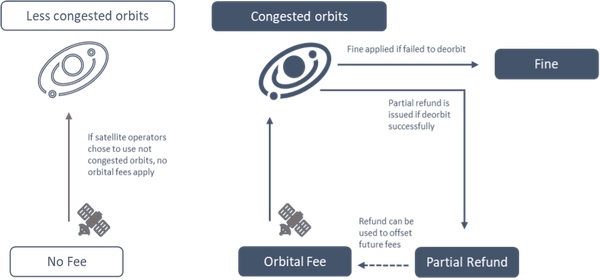

The proposed Orbital Tollway Framework draws from the concept of Orbital-Use Fees (OUF) and terrestrial congestion measures. It introduces mandatory fees for highly congested LEO subregions, assessed annually and based on an object’s duration in orbit. The fee structure operates on a deposit-refund model to incentivize operators to deorbit objects and comply with debris mitigation guidelines. Operators receive partial refunds upon successful deorbiting, while non-compliance results in penalties. Collected fees and fines are allocated to sustainability initiatives, primarily debris removal.

| A simplified model estimates that the Orbital Tollways framework could generate $5–10 billion over the next decade. |

While the framework establishes a global fee structure, management remains with national governments, similar to the existing spectrum management and usage fees. This empowers national authorities to collect and reinvest the funds into local or regional space sustainability efforts, allowing each state to control funds and their national activities. This framework seeks a dynamic equilibrium between global cooperation and national interests, while balancing industry impact with practical environmental benefits.

|

Financials: How Much Can This Generate?

A simplified model estimates that the Orbital Tollways framework could generate $5–10 billion over the next decade. This is based on annual fees ranging from $75,000 to $200,000, differentiated by orbital region, with a 40% refund for successful deorbiting, and a very conservative estimate on number of fines ranging between $750,000 and $3 million. The number of objects is based on Novaspace’s forecast, with the assumption that 80% of the objects in LEO would be in congested orbits and thus subject to the Tollway fee. While the model provides a high-level feasibility indication, more detailed analysis is required to refine the assumptions.

Viability: is it enough to clean orbits?

The short answer is yes for critical orbital areas, but no for removing all debris. Estimating the cost of debris removal remains challenging since no commercial service exists yet, and pricing depends on factors like size, mass, and orbit. KMI is the only company that published estimates ranging from $4 million to $62.5 million per object. Assuming an average removal cost of $20 million per object and allocating 60% of the lower-end projection of $5 billion to ADR, the scheme could fund the removal of 150 objects over a decade, or 15 objects per year. (It is assumed that 60% of the funds generated will be allocated to ADR activities, with the remaining 40% reserved for the administration of the scheme and other sustainability measures.) To put this figure in perspective, studies generally suggest that removing five to ten large debris objects per year could significantly reduce the risk of the Kessler Syndrome, a cascade of collisions that could make certain orbits unusable.

While this seems like a small fraction of the total debris problem, a focus on the most critical orbital zones and objects means the impact will be significant. Congestion is anticipated to peak at altitudes of 400 to 600 kilometers, but atmospheric drag naturally deorbits objects within a decade, while debris above 600 kilometers poses greater long-term challenges that future deployments will exacerbate. The highest debris concentration is at altitudes of 800 to 1,000 kilometers and 1,400 kilometers, where objects can remain for centuries. The global expert community has already identified the top 50 most-concerning derelict objects; nearly all are in these debris-dense bands. Focusing on these critical zones and objects will make the overwhelming problem more manageable, enabling effective change.

Ownership: who can take this on?

The success of any mechanism relies heavily on international collaboration, but balancing the common good with sovereign interests amid geopolitical tensions remains a challenging task. Global collaboration, particularly at the UN level, is essential to ensure the effectiveness of this framework. Without such coordination, there is a risk of “forum shopping,” where parties seek more lenient regulations in different jurisdictions, undermining the overall effort. A united approach is necessary to build a comprehensive and enforceable system that can address the debris problem globally.

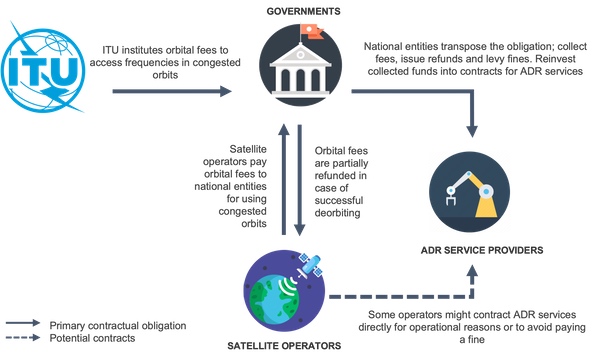

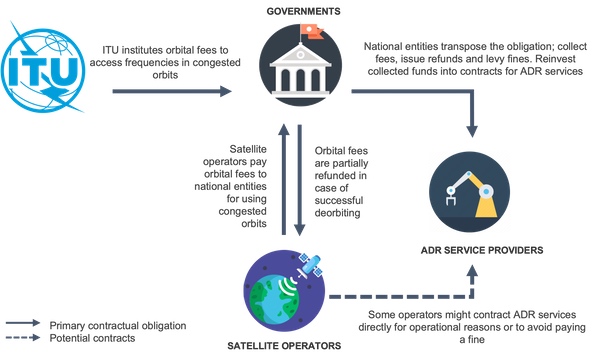

The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) emerges as the pivotal organization to establish binding global regulations, given its strategic control over the space sector’s most valuable resource: frequencies. Any reform will still require the approval of its members, but if structured as a collaborative partnership between ITU and national authorities, it stands a chance. Member states play a leading role in this scheme, with national authorities responsible for reinvesting collected funds into ADR and other sustainability initiatives at the national or regional level. This approach empowers national authorities as they retain control over their activities while addressing a pressing global issue.

Although the ITU does not regulate physical objects in space, its authority and experience position it as the ideal body to lead the development of binding global regulations. In September, ITU held its first Space Sustainability Forum to gather experts and stakeholders to discuss responsible space usage. Its proven track record, such as introducing a milestone-based approach to regulate mega-constellation deployments, demonstrates its ability to adapt to emerging challenges and drive necessary reforms.

|

Path forward: turning conversations into actions

As space exploration accelerates, binding international regulations incentivizing sustainable practices becomes essential. The Orbital Tollway framework presents a practical, scalable solution to address space debris by introducing incentives and generating funding for debris removal. While it won’t eliminate all debris, it focuses efforts on critical orbital zones and high-risk objects, making the issue more manageable and actionable.

| While this framework won’t eliminate all debris, it focuses efforts on critical orbital zones and high-risk objects, making the issue more manageable and actionable. |

This framework, as any paradigm shift, might seem daunting but reforms are inevitable—the debris issue won’t magically sort itself out. Moving from discussions to actions will require a commitment to change from industry, governments, and regulators, acknowledging that any progress will take funding and resources. Fortunately, much groundwork already exists in charters, space-agencies sponsored studies, and other research. The process is also already established given the framework’s similarity to frequency licensing procedures. What remains is to thoughtfully bring these elements together and address any remaining gaps.

Next steps could involve further economic modeling to address industry concerns about cost burdens while demonstrating potential benefits. A pilot program involving key spacefaring nations under the auspices of the ITU could then be launched to test the Orbital Tollway concept on a smaller scale. This would help overcome obstacles and refine the framework for a more practical and equitable design. Space agencies, with their extensive expertise, can actively contribute alongside industry, bringing regulators into the fold to ensure alignment and collaboration in implementing this transformational reform.

Although a debris-free orbit is unrealistic in the near term, this framework sets a viable path for progress, striking a delicate balance between global cooperation and national interests, while aligning tangible environmental benefits with realities of industry growth.

This proposal offers a structured response to the space debris problem, but the author acknowledges that the framework requires further refinement. Feedback and partnerships are welcome to help design a viable solution. For any questions or inquiries, please contact polina.shtern@community.isunet.edu.

As we enter the next era of space exploration, the focus is shifting from launching missions to constructing advanced in-space infrastructure, with one major obstacle standing in the way: the growing threat of space debris. The billion-dollar question of who bears the cost of space debris cleanup has been a longstanding issue, directly tied to uncertainty about liability and the lack of incentives. Over the past decades, this issue has been a game of hot potato between governments, space agencies, and the industry with marginal progress.

| Active debris removal faces a catch-22: high development costs and unproven technology make it difficult to attract investment, while the industry is hesitant to commit without validated, cost-effective solutions. |

Currently, there’s no clear funding mechanism for active debris removal (ADR) activities beyond the space agencies’ investments, leaving the “tragedy of the commons” unresolved. Various models, including regulatory fees, taxes, tradeable permits, and cleanup funds, have been suggested, highlighting the need for international cooperation. However, achieving consensus remains challenging especially in current geopolitical environment. Additionally, balancing environmental sustainability with industry impact is crucial for successful adoption. What follows is a framework that aims to strike this delicate balance.

The problem: space debris and the issue of incentive

The growing problem of space debris has been debated for decades and is now at the forefront of sustainability discussions. Currently, there are 36,860 tracked objects in space. With a record-high 223 launches in 2023 and projections of another 36,900 objects entering space by 2033, the collision risk is increasing exponentially. Recent incidents of space junk hitting Earth are increasingly making headlines, raising public awareness. With unprecedented space activity, rising collision risks, and the debris issue now in the public eye, it’s necessary to transition from discussions to actions.

Managing space debris requires an integrated approach, combining debris avoidance, limiting debris creation (mitigation), and debris removal (remediation). Significant progress has been made in debris avoidance, through improved tracking and development of space situational awareness (SSA) capabilities. While various debris mitigation guidelines exist, they are all non-binding, leading to voluntary and thus suboptimal compliance, especially in LEO. Initiatives like ESA’s Zero Debris Charter and the UK’s Astra Carta are aimed at encouraging sustainable practices, but participation remains voluntary, attracting industry players with existing commitment to sustainability. These initiatives also do not address accumulation of debris over the past decades.

While debris avoidance and mitigation efforts have seen some momentum, remediation, or ADR, has significantly lagged behind. The root of the issue lies in the regulatory environment, which lacks both incentives and penalties to promote compliance and sustainable practices. Despite widespread recognition of the problem, the absence of binding regulations, financial incentives, and proven technologies continue to hinder meaningful progress. ADR faces a catch-22: high development costs and unproven technology make it difficult to attract investment, while the industry is hesitant to commit without validated, cost-effective solutions. This creates a vicious cycle, with supply side requiring demand to mature, but the demand side is reluctant to invest without proven capabilities and regulatory pressure. Without intervention, the market has no inherent need to bridge this gap. Therefore, government action—through binding regulations and incentives—is essential to break this deadlock and enable the development of the ADR market.

Pioneering companies like Astroscale, Starfish Space, Kall Morris, and D-Orbit are diligently working to prove the technology, relying on a handful of government sponsored missions. The question remains: can they sustain their efforts long enough for the necessary market conditions and regulatory framework to materialize?

The solution: Orbital Tollway Framework

The proposed Orbital Tollway Framework draws from the concept of Orbital-Use Fees (OUF) and terrestrial congestion measures. It introduces mandatory fees for highly congested LEO subregions, assessed annually and based on an object’s duration in orbit. The fee structure operates on a deposit-refund model to incentivize operators to deorbit objects and comply with debris mitigation guidelines. Operators receive partial refunds upon successful deorbiting, while non-compliance results in penalties. Collected fees and fines are allocated to sustainability initiatives, primarily debris removal.

| A simplified model estimates that the Orbital Tollways framework could generate $5–10 billion over the next decade. |

While the framework establishes a global fee structure, management remains with national governments, similar to the existing spectrum management and usage fees. This empowers national authorities to collect and reinvest the funds into local or regional space sustainability efforts, allowing each state to control funds and their national activities. This framework seeks a dynamic equilibrium between global cooperation and national interests, while balancing industry impact with practical environmental benefits.

|

Financials: How Much Can This Generate?

A simplified model estimates that the Orbital Tollways framework could generate $5–10 billion over the next decade. This is based on annual fees ranging from $75,000 to $200,000, differentiated by orbital region, with a 40% refund for successful deorbiting, and a very conservative estimate on number of fines ranging between $750,000 and $3 million. The number of objects is based on Novaspace’s forecast, with the assumption that 80% of the objects in LEO would be in congested orbits and thus subject to the Tollway fee. While the model provides a high-level feasibility indication, more detailed analysis is required to refine the assumptions.

Viability: is it enough to clean orbits?

The short answer is yes for critical orbital areas, but no for removing all debris. Estimating the cost of debris removal remains challenging since no commercial service exists yet, and pricing depends on factors like size, mass, and orbit. KMI is the only company that published estimates ranging from $4 million to $62.5 million per object. Assuming an average removal cost of $20 million per object and allocating 60% of the lower-end projection of $5 billion to ADR, the scheme could fund the removal of 150 objects over a decade, or 15 objects per year. (It is assumed that 60% of the funds generated will be allocated to ADR activities, with the remaining 40% reserved for the administration of the scheme and other sustainability measures.) To put this figure in perspective, studies generally suggest that removing five to ten large debris objects per year could significantly reduce the risk of the Kessler Syndrome, a cascade of collisions that could make certain orbits unusable.

While this seems like a small fraction of the total debris problem, a focus on the most critical orbital zones and objects means the impact will be significant. Congestion is anticipated to peak at altitudes of 400 to 600 kilometers, but atmospheric drag naturally deorbits objects within a decade, while debris above 600 kilometers poses greater long-term challenges that future deployments will exacerbate. The highest debris concentration is at altitudes of 800 to 1,000 kilometers and 1,400 kilometers, where objects can remain for centuries. The global expert community has already identified the top 50 most-concerning derelict objects; nearly all are in these debris-dense bands. Focusing on these critical zones and objects will make the overwhelming problem more manageable, enabling effective change.

Ownership: who can take this on?

The success of any mechanism relies heavily on international collaboration, but balancing the common good with sovereign interests amid geopolitical tensions remains a challenging task. Global collaboration, particularly at the UN level, is essential to ensure the effectiveness of this framework. Without such coordination, there is a risk of “forum shopping,” where parties seek more lenient regulations in different jurisdictions, undermining the overall effort. A united approach is necessary to build a comprehensive and enforceable system that can address the debris problem globally.

The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) emerges as the pivotal organization to establish binding global regulations, given its strategic control over the space sector’s most valuable resource: frequencies. Any reform will still require the approval of its members, but if structured as a collaborative partnership between ITU and national authorities, it stands a chance. Member states play a leading role in this scheme, with national authorities responsible for reinvesting collected funds into ADR and other sustainability initiatives at the national or regional level. This approach empowers national authorities as they retain control over their activities while addressing a pressing global issue.

Although the ITU does not regulate physical objects in space, its authority and experience position it as the ideal body to lead the development of binding global regulations. In September, ITU held its first Space Sustainability Forum to gather experts and stakeholders to discuss responsible space usage. Its proven track record, such as introducing a milestone-based approach to regulate mega-constellation deployments, demonstrates its ability to adapt to emerging challenges and drive necessary reforms.

|

Path forward: turning conversations into actions

As space exploration accelerates, binding international regulations incentivizing sustainable practices becomes essential. The Orbital Tollway framework presents a practical, scalable solution to address space debris by introducing incentives and generating funding for debris removal. While it won’t eliminate all debris, it focuses efforts on critical orbital zones and high-risk objects, making the issue more manageable and actionable.

| While this framework won’t eliminate all debris, it focuses efforts on critical orbital zones and high-risk objects, making the issue more manageable and actionable. |

This framework, as any paradigm shift, might seem daunting but reforms are inevitable—the debris issue won’t magically sort itself out. Moving from discussions to actions will require a commitment to change from industry, governments, and regulators, acknowledging that any progress will take funding and resources. Fortunately, much groundwork already exists in charters, space-agencies sponsored studies, and other research. The process is also already established given the framework’s similarity to frequency licensing procedures. What remains is to thoughtfully bring these elements together and address any remaining gaps.

Next steps could involve further economic modeling to address industry concerns about cost burdens while demonstrating potential benefits. A pilot program involving key spacefaring nations under the auspices of the ITU could then be launched to test the Orbital Tollway concept on a smaller scale. This would help overcome obstacles and refine the framework for a more practical and equitable design. Space agencies, with their extensive expertise, can actively contribute alongside industry, bringing regulators into the fold to ensure alignment and collaboration in implementing this transformational reform.

Although a debris-free orbit is unrealistic in the near term, this framework sets a viable path for progress, striking a delicate balance between global cooperation and national interests, while aligning tangible environmental benefits with realities of industry growth.

This proposal offers a structured response to the space debris problem, but the author acknowledges that the framework requires further refinement. Feedback and partnerships are welcome to help design a viable solution. For any questions or inquiries, please contact polina.shtern@community.isunet.edu.

Original article from https://www.thespacereview.com/article/4902/1